The Precision Trap: Time, Money, and Data Modeling

Problem solving is still the core of engineering. Tools change, frameworks change, and now AI is in the loop, but the quality of our decisions still decides the outcome.

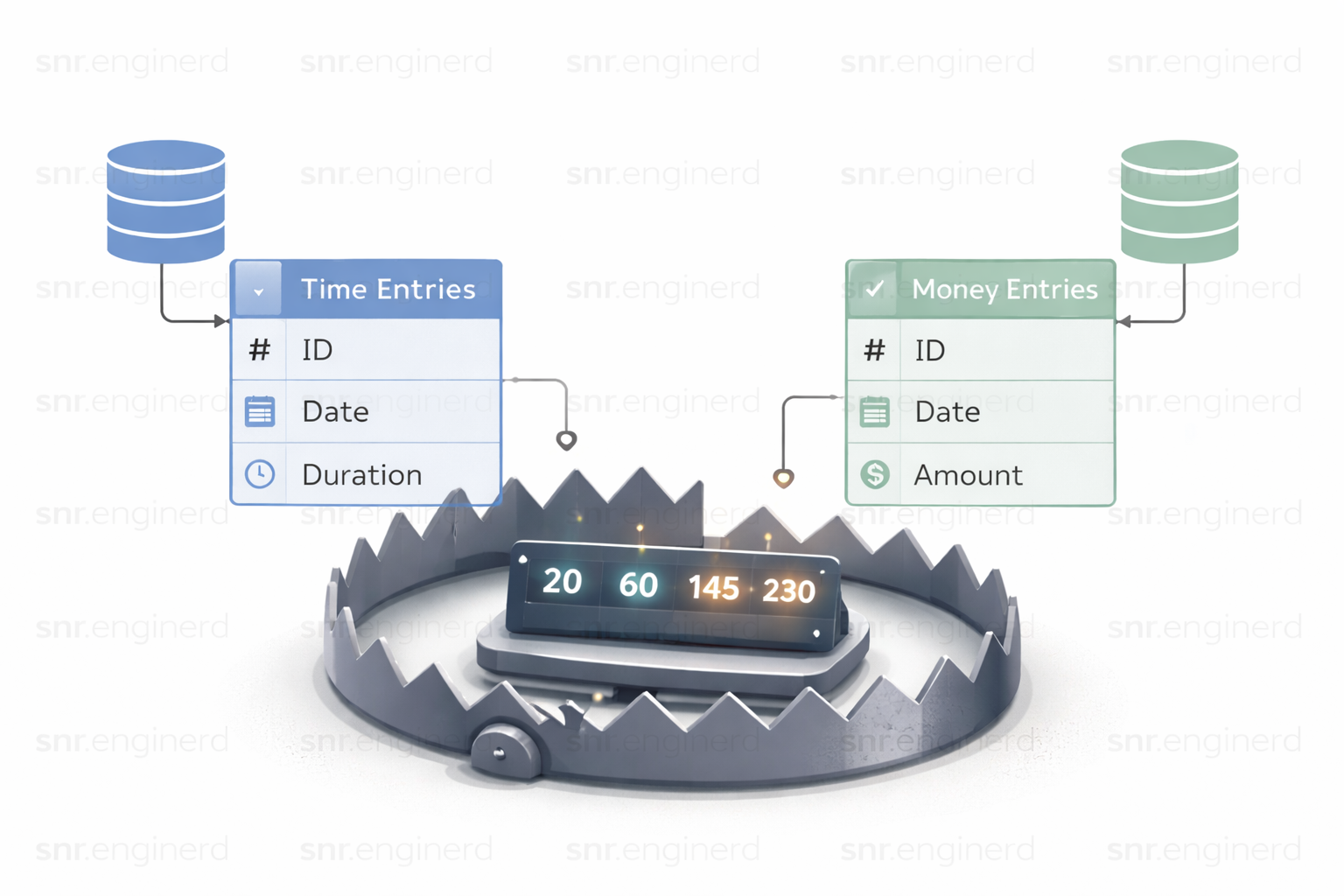

This post is about one design decision that looks small at first and gets expensive later: how we store time and money.

The practical problem

Imagine a time tracking app.

- A user logs a time entry like

1h 25m - The report screen shows each entry

- The report also shows a total at the bottom

Looks simple. But if the storage model is wrong, totals drift and trust drops.

The same pattern shows up in financial systems. If the value is money, even 0.01 matters.

What not to store

A raw string like 1h 20m is human-friendly but hard to compute with. Summing, filtering, and converting become awkward fast.

A timestamp or datetime type is also the wrong fit here. 2026-02-01 00:20:00 describes a point in time, not a duration.

Float, decimal, or integer?

This is where teams usually debate.

Float

FLOAT values are approximate in most databases because they are binary floating-point numbers. Values like 0.1 cannot be represented exactly, so tiny errors can appear during repeated math and aggregation.

Decimal

DECIMAL is exact base-10 with fixed precision and scale. That makes it a strong choice for financial values.

But decimal still requires careful design. If you store time in hours with limited scale (for example two decimal places), 20 / 60 might become 0.33. Converting back gives 19.8 minutes, and now you need extra rounding rules.

So the issue is not that decimal is "bad." The issue is that storing durations as fractional hours introduces conversion and rounding complexity.

Integer (smallest unit)

The most robust approach I have seen is storing values as integers in the smallest unit.

- Time: store minutes (or seconds if needed)

- Money: store cents (or smallest currency unit)

Examples:

20m->201h->602h 25m->145

This avoids floating-point drift and keeps aggregation simple.

A schema-first example

Here is a simplified version of the same idea at the database layer:

-- Risky for precision-sensitive totals (approximate floating-point)

CREATE TABLE time_entries_float (

id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

task_id BIGINT NOT NULL,

hours_float FLOAT NOT NULL

);

-- Better than FLOAT, but hours-as-decimal still needs conversion rules

CREATE TABLE time_entries_decimal (

id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

task_id BIGINT NOT NULL,

hours_decimal DECIMAL(10,2) NOT NULL

);

-- Recommended: store duration in smallest unit

CREATE TABLE time_entries (

id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

task_id BIGINT NOT NULL,

duration_minutes INT NOT NULL CHECK (duration_minutes >= 0)

);

-- Recommended: store money in smallest unit

CREATE TABLE invoices (

id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

customer_id BIGINT NOT NULL,

amount_cents BIGINT NOT NULL CHECK (amount_cents >= 0)

);With smallest-unit integers, totals stay straightforward:

SELECT task_id, SUM(duration_minutes) AS total_minutes

FROM time_entries

GROUP BY task_id;Why this matters

If you ever shipped a version that stored this the wrong way, you are not alone. Most of us learn this in real projects, not tutorials.

Getting better at engineering is often just this:

- notice a bug pattern

- understand why it happens

- choose a better model next time

That is growth. Nothing to be embarrassed about.

Final thoughts

When precision matters, model for computation first and format for display later. For time and money, smallest-unit integers are usually the safest default. It keeps logic simpler, totals trustworthy, and debugging sessions shorter.